The mid-to-late 1970s and the 1980s also witnessed protest movements in West Germany and Greece. The women’s liberation movement and the gay liberation movement, which had appeared around 1968 in West Germany and in the mid-1970s in Greece, continued to be active. Feminists politicised issues regarded as ‘personal’ and were particularly concerned in those two countries with the freedom of women to perform abortions and with the rape that numerous women experienced.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, West German state institutions began to consider the integration of migrants more seriously. This development was a change compared to what the migration bureaucracy claimed in the previous years, namely that migrant workers are ‘guests’ and ‘foreigners’ to West German society. However, they developed various integration proposals. Such proposals were usually just directed at migrants often did not come with a reflection on how German society was changing or should be changing. In this vein, integration proposals were frequently patronising and coupled with culturally racist perceptions that migrants were forming ghettos (Reinecke 2021) or that migrant families could not adjust easily to the realities of West Germany (Stokes, 2022). The flexible ‘waiting period’ that the Labour Ministry implemented in 1979 exemplified the latter perception. Migrant teenagers had to wait for two years to access the labour market unless they took action, such as attending vocational courses (the so-called flexible waiting time). The Ministry argued that this measure helped migrant teenagers to integrate (Stokes, 2022). Meanwhile, in 1974 the federal government reformed the provision of children allowances for migrant workers to offer reduced amounts for their children who did not live in West Germany. Thus, the West German government demotivated the maintenance of transnational families (Stokes, 2022). In any case, the Christian Democratic parties, which led the government from 1982 to 1998, firmly believed West Germany was ‘not a country of immigrants’ (Wiliarty, 2021) and, thus, did not show a keen interest in integration effort of migrants at the federal level.

Meanwhile, the circumstances of some Greek migrants who stayed in West Germany also changed. Although several of them continued to be workers, a growing number of Greek migrants began to run their businesses, usually a restaurant (Möhring, 2012).

As the 1970s progressed, political and economic changes in Greece also affected the condition of Greek migrants. In 1974, the dictatorship collapsed in Greece, followed by a stable democracy. Parties, including the Communist Party of Greece, became legal in 1974. Meanwhile, the Greek economy had been improving since the 1960s. Able to find a job in Greece and/or no longer afraid to express their political views in public, several Greek migrants in West Germany remigrated to Greece. Overall, the number of Greeks in West Germany decreased from 407,614 in 1973 to 274,973 in 1988 (source: The Federal Statistical Office, Germany).

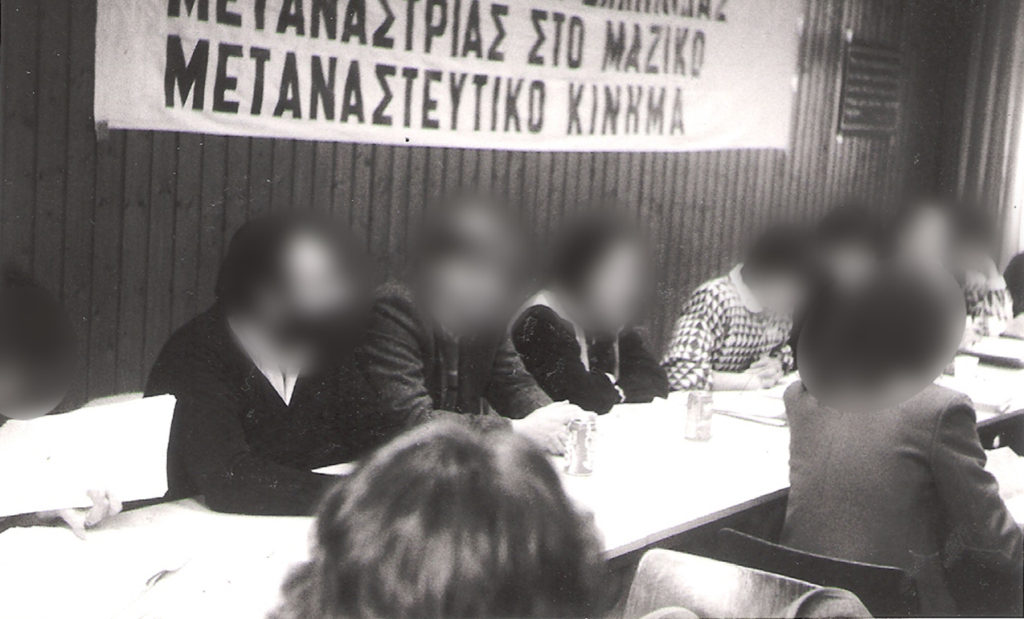

Restrictions on migrant families and the improving social status of some Greek migrants changed the focus of their demands to an extent. Although factory strikes and squats persisted, migrant communities growingly focused on the conditions of migrant families. A vital issue for migrant protests, particularly in 1974-1981, was the creation and retention of national schools where the children of migrants could be taught in Greek. Greek communities, including the OEK, namely the Federation of Greek Communities in West Germany, held protests and even hunger strikes in support of Greek schools. OEK would also lobby the institutions to promote such schools. Such protests did not necessarily end the collaboration between Greek migrant, other migrant and German activists, which had become more intense in the previous years. Greek and West German trade unions, including the DGB (Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, German Trade Union Confederation), mobilised to create bilingual schools where Greek and German teachers would collaborate (Adamopoulou, 2022). Meanwhile, the OEK reached out to the DGB to promote together the rights of Greek migrant [heterosexual] women in West Germany. The relevant initiatives of the OEK did not relate to the Feminist movement that was active in West Germany and in Greece in this period and did not touch upon issues of sexuality.

Meanwhile, less conspicuous forms of challenging the authorities appeared among Greek migrants. Crucially, the growing in number non-German restaurant owners encountered a hostile political and economic environment. As a result, they used legal opportunities available to them and resorted to illegal activities, such as using a West German strawman as the nominal owner of their business in order to pen the latter (Möhring 2014). Thus, while not openly protesting in this case, they did resist the restrictions that the West German state institutions and society posed to them.

Material

14: Booklet (cover page) on the problems facing the Greek youth in the Federal Republic of Germany. Courtesy of OEK.

15: OEK, women’s committee: Booklet (cover page) on Greek migrant women and the trade unions. Courtesy of OEK.

16: Meeting of the OEK on Greek migrant women. Courtesy of OEK.

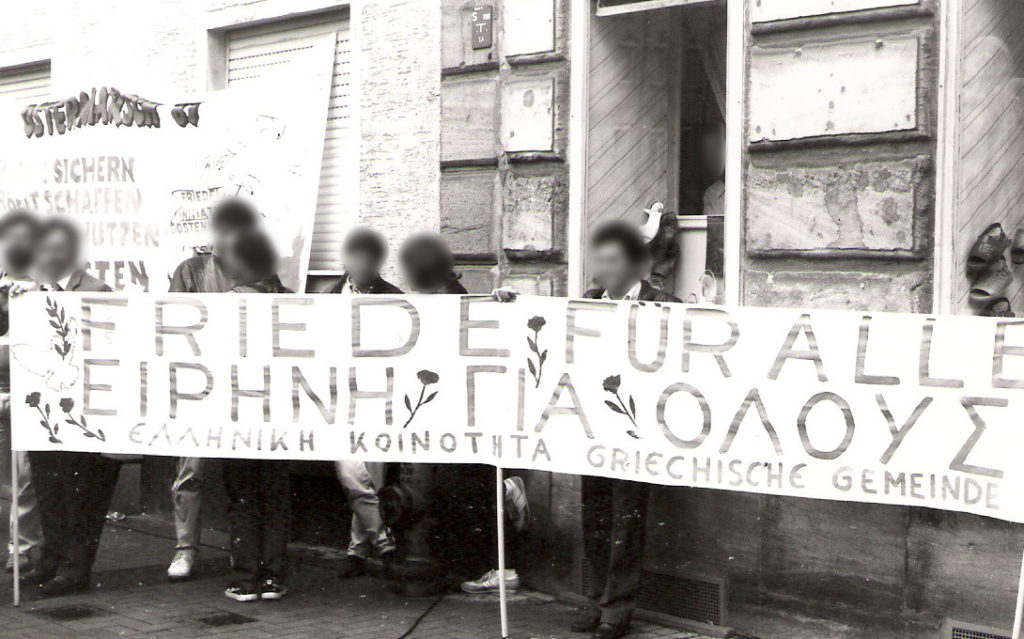

17: Ostermarsch, 1987. Participation of a Greek Community. Courtesy of OEK.

18: Multinational march on May 1st. Courtesy of OEK.

19: Announcements of the OEK in the aftermath of its 7th congress in 1980. Courtesy of OEK. Topics mentioned:

- The ‘need for unity’ among Greek migrants

- The right of Greek migrants to vote in West Germany.

- Children allowances and migrants

- Migrant youth issues